Pointlessness is powerful

Plus MF Doom, Christopher Nolan, Little Britain and more

Crammed into one of three occupied seats in the front of a medium-sized taxi, with an hour and forty-five minute journey ahead of me, my train cancelled and my puffer jacket a clearly terrible choice given the fifteen degree heat, one question ran persistently through my mind: how bad can things actually get?

That was on Sunday evening, having spent a lovely weekend at my brother’s in Norwich, but needing to trek back home with a nice smooth journey on the British rail network absolutely off the cards.

Obviously I exaggerate. Things could’ve been much, much worse. I had a copy of the New Statesman wedged between the car door and my sweaty, boxed-in left thigh, and I was the proud owner of a small pile of new records no doubt sliding around in the boot, ready to be stolen or destroyed at any moment. Perspective is important.

Though I do joke, journeys like that have often made me realise the value of physical media: I wasn’t about to fumble in my pockets for my phone, given the close quarters me and all those rail replacement strangers were crammed into, so I was grateful I had a magazine in my lap. I can’t tell you the number of times my mobile or laptop have died in the middle of a long journey and I’ve been grateful to find a novel or an issue of the Guardian Weekly in the bottom of my rucksack. Collecting vinyl has completely altered the way I consume music, too. Physical media are great.

The arguments levelled against them continue to stand, though. It’s difficult to justify shelling out a fiver on a political weekly when I can get everything for free seconds after it broke online, and while I’ve never found it even slightly difficult to trade money for records, from a purely financial standpoint collecting physical music makes basically no sense at all.

Which got me thinking. Maybe the reason physical media are so great is because they’re essentially pointless, not actually despite it. That’s the subject of this edition’s column, which you can read below.

There’s also some fresh music recommendations for CE13, including a pair of new albums released in the last couple of weeks and two older ones, spanning house, techno, hip-hop and more. Scroll to the bottom for those.

Enjoy!

Finding purpose in the pointlessness: the beauty of modern media’s non-necessity

Physical media has absolutely no right to exist; perhaps that’s why I love it so much

Collecting DVDs seems like an odd practice to me. I know how that sounds - I’ve written a great deal about my love for vinyl in this newsletter in the past - but I just don’t get it.

It’d be futile for me to try to explain the actual reasons for my feelings: I do consider myself a film fan, but in the same way I might denounce the music casual who laughs off my costly obsession with audible plastic, I’m sure a headsy defender of the moving image could dismantle my argument with ease.

Big name directors Guillermo del Toro and Christopher Nolan have talked up the benefits of physical media in the past, emphasising the importance of keeping your own physical archive for fear of having your favourite art digitally stolen away at the discretion of streaming platforms.

When I first read those quotes I was a bit sceptical; they seemed slightly paranoid, given that most providers give a pretty decent warning before removing titles, and that even when they don’t you can almost always buy those films online for less than a fiver.

But as I thought on it a little longer, examples of the kind of media revocation del Toro and Nolan talk about came to mind fairly quickly. British duo David Walliams and Matt Lucas’ hit series Little Britain and Come Fly With Me were removed from Netflix in 2020 owing to their controversial and often dated contents, and for a time were only viewable by those who owned hard copies.

While those programmes are now available to watch on a couple of streaming platforms, changing social ideas and identity politics will surely see other works fall through the cracks of cultural history. Those projects might only be preserved in physical formats.

There’s a number of examples in electronic music, too: just last week I searched for Four Tet’s Morning/Evening to find it’d been removed from Spotify. I was grateful at that moment that I had it on vinyl: I’ve always found actually spinning records a far less clunky experience than listening on YouTube, and doubly in the months and years since the video platform seemed to have upped the frequency of its adverts.

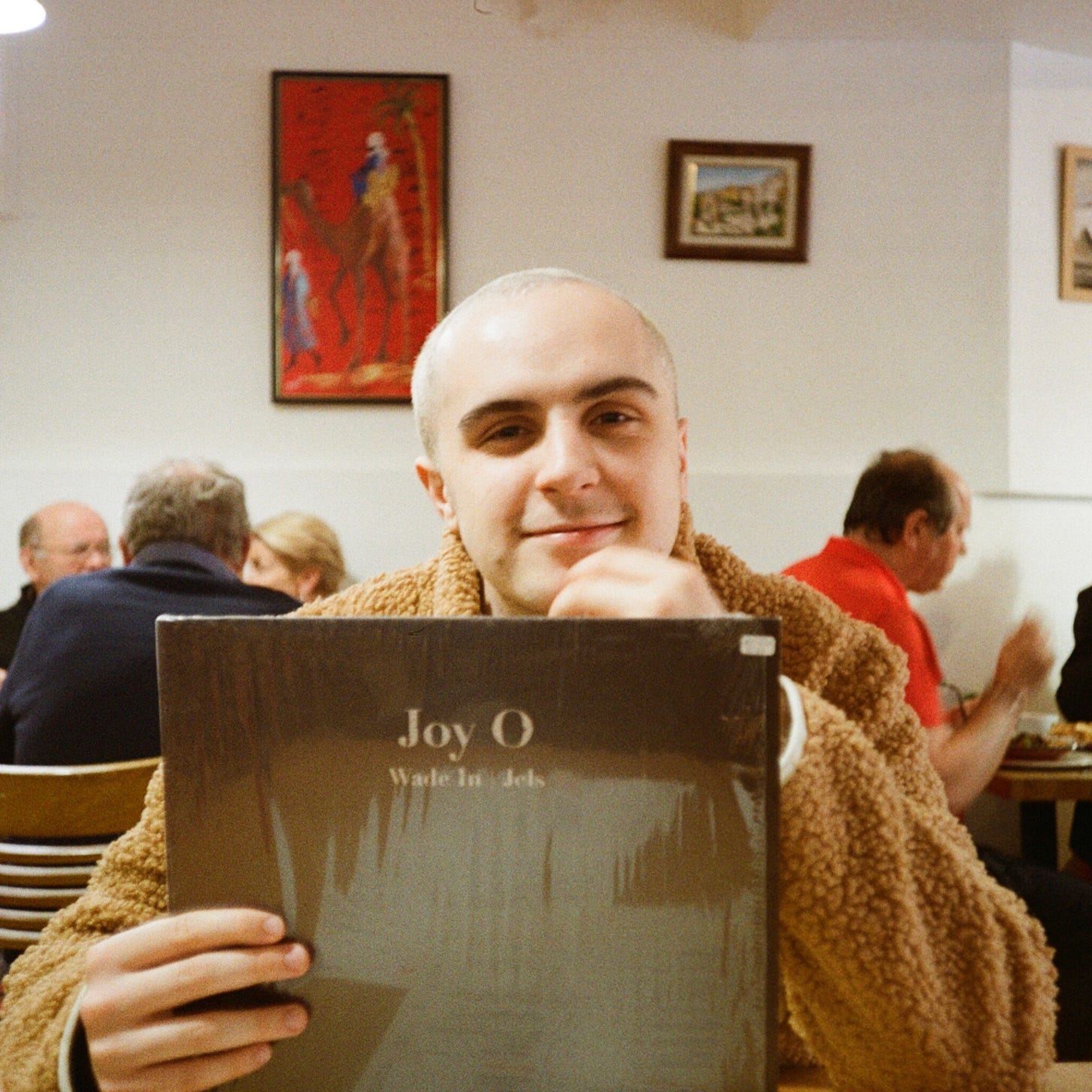

My brother’s the proud owner of the vinyl edition of Joy Orbison’s very early two-tracker Wade in / Jels, which isn’t even on Bandcamp - another victory for vinyl defendants.

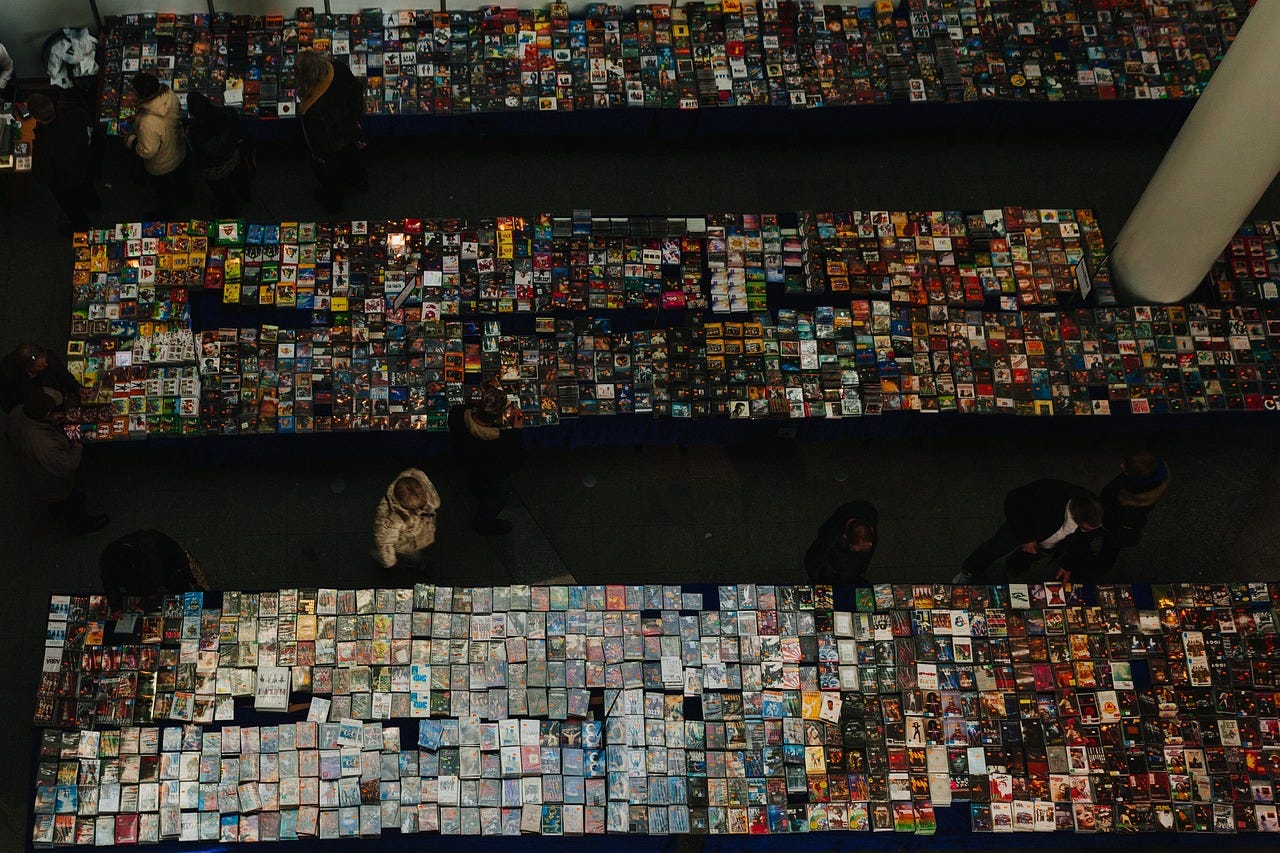

I could go into detail about physical media’s other purposes (the ability to hold the art you love in your hands; the rare occasions that records and magazines turn out to be profitable investments; the aesthetic treat of a thick stack of vinyl or a shelf piled high with books) but I think that would see me fall into a trap all too familiar to so many collectors. To justify the existence of physical media simply by explaining their practical uses does them a disservice: in an age in which there’s really no excuse to do so, part of the beauty of pouring time and money into the collection of these things is that it makes no sense at all on a logical level.

I think that’s part of why I can’t really connect with DVDs or CDs in the way I do with records and magazines. When I grew up, you had two options if you wanted to watch a film: either you saw it in the cinema, or you somehow got your hands on the DVD.

I lived through the practical era of DVD and Blu-ray. I experienced all the impracticalities that went with it, and I saw the industry invent a better way (for consumers, at least).

My experience with vinyl was very different. When I started school in the mid 2000s, no one was interested in vinyl. No one had a record player, and while admittedly I wasn’t exactly at the heart of any music fandom circles, I’m not sure there was much buzz about a vinyl resurgence by the time I started to consciously seek out and buy my own music.

For as long as I’ve cared about music, vinyl has always seemed a bit pointless, which is why I’m liberated to love it so much. I never buy a record because I need to, but because I’m so intrigued by it, or I already enjoy it so much, or I’ve heard such great things about it, I’m willing to part with my own money when from a logical standpoint there’s no real reason to.

That’s the real thrill of buying and keeping and playing these records: I’ve never actually needed to, but for some reason I’m constantly compelled to, and almost always rewarded.

CrateEater Recommends: 18/10/24

A handful of projects I’m into right now. Always some new music, always some classics - let’s dig in.

MM…Food is one of my favourite hip-hop records, and with its 20th anniversary - as well as a heftily lengthened new edition - coming next month, it seemed the right time to add the album to my collection. Daniel Dumile’s second LP as MF Doom is crammed full with heaters: ‘Beef Rap’ is one of the greatest album openers of all time, ‘Deep Fried Frenz’ is still underrated despite its lofty reputation, and ‘Rapp Snitch Knishes’ takes the strange concoction of soaring electric guitar and laid back rhymes and somehow produces something not just palatable but genuinely excellent. One comment from a fan on Bandcamp sums it up better than I can: “[This is] the audio equivalent of waking up on a Saturday morning, pouring yourself a bowl of cereal and watching cartoons.” It’s a real treat.

One third of the leadership of legendary UK label Hessle Audio, Pearson Sound - real name David Kennedy - has been doing great things in electronic music for some time. Despite decades in the business, he’s only released one full-length solo project: this, his self-titled debut album from 2015. I found the LP in the middle of a stack of techno records in the fantastic shop Soundclash Records in Norwich, and hastily added it to the pair of discs already stowed under my arm (those being the aforementioned Mm…Food and Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas To Heaven). While Pearson Sound is probably best described as deep techno, it’s a little more experimental than that, melting down and reforming industrial but groovy percussion-heavy instrumentals with impressive results.

2017 single ‘Final Credits’ is easily Midland’s biggest track. The live-drummed, soul-sampling hit is true disco at its core: it’s slower than most house music, but retains the celebratory feel of that genre, and its samples call back to a time of groove and glam on Black and Queer American dancefloors. You might expect that Midland would channel that sound on his debut album, but not so.

Fragments of Us, released 4 October on Graded, is truly electronic, variably danceable, and often incredibly tender. While it does just sound incredible, it is also rooted in unimaginable cultural and individual pain. Amongst a number of significant voices, the album samples a narrator explaining the enactment of Section 28, a series of laws introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in 1988. Section 28 prohibited the “promotion of homosexuality” in public life, and included severe restrictions on school education surrounding homosexuality. Fragments of Us does the incredibly difficult job of being both a beautiful listen and a poignant reflection on Queer life.

While Caribou’s latest work isn’t exactly groundbreaking, it’s thoroughly enjoyable, and includes a number of dancefloor-ready tunes which will surely see plenty of play in nightclubs and beyond throughout the rest of 2024. Like Floating Points’ September album Cascade, Honey sees an underground favourite priotitise all-out danceability, and not in the total absence of innovation or experimentation. Well worth a listen.

That’s all for this week. Thanks as always!

Luke